Pedro Tavares

Since the 1970s, prolific American director Lewis Klahr has combined animation techniques with avant-garde cinema, which in recent years has helped to retell and reread modern American history. Owner of a unique work, Klahr walks through pillars of American pop culture such as comics, pulp fiction, film noir and has a close relationship with sound – or lack of it. I talked a little with Lewis about his work in general, and, mainly, about his relationship with silence, dyssynchrony, absence, noise, tracks, etc.

This issue of the magazine is about cinema and silence.

Hmmmmnnnn…… I think film silence is still a highly specific sound. For instance, I recently completed a soundtrack for a new film titled Thin Rain. Inspired by Film Noir, Thin Rain tells the story of an amnesiac protagonist who loses his memory after being hit in the back of his head by a gun handle. Before this attack, the soundtrack has symphonic music. Once the protagonist loses his memory the music ends and is replaced by the white noise sound of a blank analog 16mm optical track. We call this optical “blank” but it is full of sound: pops, scratches, and hisses!

Silence was something that caught my attention when I saw one of your films for the first time in a theater. I believe it was Sixty-Six.

I primarily use silence in Sixty-Six as a conventional separator of the individual films, a short duration (5-10 seconds) palate cleanser. But the film Ambrosia, which occurs in the latter part of Sixty-Six, is silent and required careful sequencing to get it effectively positioned because getting a silent film to effectively follow a sound film is an aesthetic challenge. The films in Sixty-Six that directly precede Ambrosia needed to gradually quiet down to provide a successful lead in. Whereas, the film that followed Ambrosia, and returned to sound, had much greater flexibility in terms of what its soundtrack could contain.

I would like, if possible, if you could talk a little about the relationship of duplicity that your images involve and the path that I feel is emancipated

from the composition of the images by your use of sound.

I wouldn’t describe my relationship to sound and image as “duplicitous” but that’s an interesting thought. I’m not very clear about what you’re describing or asking but taking my best guess at what I suspect you mean– I am rarely interested in creating a “realistic” or full soundscape. Often my approach results in a limited or focused use of sound in which only some parts of the sound that an image may suggest are represented aurally. The parts of the image that are not represented remain silent and visual.

In your films there is usually a very consistent break in silence, like your most recent film The Blue Rose of Forgetfulness, which reminds me of a musical and is soon at the confluence of silence and a narrative in very strong codes.

In The Blue Rose of Forgetfulness I think the clearest example of what you are asking about occurs in the 4th film of the series— Blue Sun. This film uses as its source material images from a Secret Agent comic book from the late 1960’s. I’ve used a lightbox to illuminate both sides of the comic book page and reveal superimpositions. In my shooting I then seek to harvest the most interesting of these superimpositions.

Blue Sun’s soundtrack has 3 different sections with the first being the playing in reverse of Sibelius’ The Swan of Tuonella. After 8 minutes the piece concludes and this lush orchestral music gives way to an ultra mundane streetscape I recorded of birds chirping and cars passing that lasts for approximately 5 minutes. After this, for only the last 30 seconds of imagery, there is silence which creates a kind of hush, or an absence, like the air escaping a balloon. Full viewer attention is now briefly given to the images. All 3 approaches to sound significantly alter the way the viewer experiences the image. This shifting of viewer engagements throughout all my films is a major part of their aesthetic engagement and structuring.

I agree I can be described as making “musicals”. On the most obvious level when I use pop songs as my soundtracks the lyrics usually tell a story and often act the way dialogue or voice over narration would in a narrative film. But just as in narrative filmmaking where the script is not the film, the lyrics are not the film here either. My images alter, contradict and also support the lyrics. For example, in my 2010 film Nimbus Smile I use the iconic Velvet Underground song Pale Blue Eyes as the soundtrack. However, the comic book female I’m using as my protagonist very clearly has black eyes not blue eyes. This raises questions about whether she’s the woman being sung about. Simultaneously the mise en scene is filled with images that contain different shades of blue. I hope the audience will notice and question why this color displacement of blue from the female protagonist’s eyes in the lyrics to the décor is occurring and what it might express.

In Circumstantial Pleasures it is not a change to silence that happens but a large change that occurs in a different way through the train trip and the sounds of warning announcements and the engine itself. How do you think about this type of composition?

Circumstantial Pleasures differs from most of my other features in that it is concerned with describing the contemporary world and only the very recent past. High Rise, the train film you refer to above, is the only film in the entire series that doesn’t use music for its soundtrack. It is a live action film shot on my phone in China during the summer of 2016 on a high speed train traveling to Beijing. Filmed in one continuous, nearly two minute shot are the passing towers of a massive apartment complex that is under construction. This apartment complex has no audible sound. The sync sound heard in High Rise is of the offscreen space of the train tracks and the interior train car in which I am traveling. This film provides a strong contrast from the other films that have preceded it in the series since none of them are live action and all use single framed, collage imagery. But a funny thing happens– the buildings under construction are so cartoon like in appearance that various audience members have asked me what exactly they are seeing—whether High Rise is also an animation and not a live action film.

What fascinates me about your films is that there is this kind of sound displacement, but at the same time there is a very strong connection with a specific time frame such as Film Noir. Your soundtracks reinforce a journey into the past, but what you do with silence is a work that is based on contemporaneity in my view, especially when we talk about experimental filmmakers. Do you think there’s any sense in that?

I do, it’s an interesting perception. Being an associational thinker and montagist I very much aim to create experiences that can be understood simultaneously in a number of different ways, even if they may appear to be contradictory or paradoxical. I also include visual anomalies in my films of present day imagery to make it clear that my films despite being historically descriptive are being made in the present.

Does sound in experimental cinema have any influence on your work?

Yes, of course. The most obvious influence being my use of music, both pop songs and classical. I am especially indebted to the films of Kenneth Anger, Bruce Conner, Jack Smith, Ken Jacobs and Harry Smith. The way all of the above filmmakers used music as a collage source material and also as an essential element of their montage was seminal for me as a developing filmmaker.

However, I think it’s worth noting that when I decided to make my film soundtracks as music-centric as they’ve been for the last 30 years, this was considered a very unacceptable choice by the experimental film world. There was this idea (less predominant now but still existing) that being music-centric was outmoded, and too easy an approach (like it was cheating LOL). That being music-centric was something experimental film had outgrown and left behind, rather than being a genre choice with a rich and fertile tradition and history of its own with very high standards of effectiveness just like any other genre.

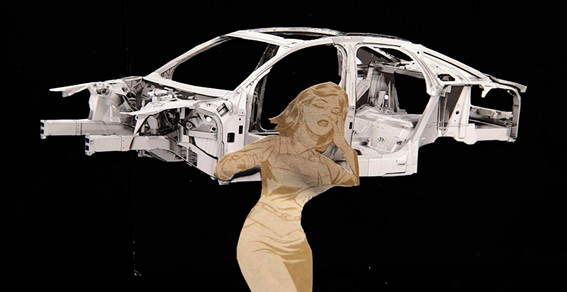

Logically, your films are intrinsic to the experience of reading comics alongside the projection that can be composed of a soundtrack or not.

My characters often speak in the word balloons of comic books. Sometimes what they speak is not meant to be understood which is why words are crossed out or sentences are interrupted. These speech bubbles are merely meant to indicate that speech is occurring (there are many similar moments in narrative films where dialogue is inaudible). Also, sometimes I cut out a comic book character and I leave attached some words they are speaking in the story they from which they were taken. These words rarely relate to the story my film is telling. However, these word remnants do clearly suggest the history of my appropriated characters. I want the audience to think about this history of the original context my characters existed in.

My characters speaking in comic book word bubbles rarely speak in voices heard on the soundtrack. I really enjoy this kind of displacement of having sound appear visually. The specificity of this visualization I try to make as precise as possible. For instance, there is a moment in Alcestis, another film from The Blue Rose of Forgetfulness, where the title character has an orgasm and she says “Oh, Oh, Oh”. This is handwritten in pen whereas normally, when Alcestis speaks, it appears as typed words in speech bubbles. The handwriting conveys both the intimacy and individuality of this sexual moment.

And I would like to know how much you want to control the spectator’s interpretation of your film’s meaning and whether this is a consideration for you during the process of creation?

Yes, I do consider the reception of the spectator while making my films. For example, the description of the dialogue in Alcestis I’ve just given above might or might not be understood by an audience. I’m often telling myself a story in my aesthetic choices that I know will only be partially understood by most of my viewers. Through long experience of working this way I’ve learned that each individual spectator will assemble the images to the idiosyncratic specifics of their interests, experience and subjectivity. In effect they often make up their own version of the story that has little to do with the one I’m trying to convey. I am comfortable with this openness of interpretation and consider it a strength of my storytelling.

Speaking of The Blue Rose of Forgetfulness specifically, how did you come up with the soundtrack for the film and how was working with these songs as a dramatic device? There is a very interesting use of de-sync in it.

As I created the sequence for The Blue Rose of Forgetfulness I found the flow of the music and sound became the priority for how the films would allow me to sequence them. I was shocked by how specific this flow was. It is probably the strongest sequencing of my films sonically that I have ever created. I’m especially pleased with the flow of the first 4 films—Monogram; Swollen Kisses; Capitulation’s Promise; Blue Sun. This is not something I intentionally set out to accomplish but discovered as an essence/aspect of these films as I attempted to sequence them. It was very surprising to me– I never would have thought to sequence them the way I have. For instance, I imagined that Capitulations Promise, the film with the Lana Del Rey song, could never follow Swollen Kisses the film with the Julie London songs. I thought they would need to be separated because of their similarity of feeling and mood. Instead, I discovered the effectiveness of their proximity intuitively through an arduous process of trial and error which required multiple viewings of different trial sequences. There was an editorial ruthlessness and honesty required to get it right. Very hard work!

As for what you’re calling de-sync (I have not heard this term before and like it very much!) I hold the bar very high in terms of having reasons to use a particular piece of music, especially pop songs. It is often important that the image moves in and out of sync with the music’s beat to create a contrast and counterpoint rhythmically. As I’ve stated I am very interested in changing a viewer’s engagement of the image as a film progresses– so moving from music to silence or sound effects, often produces a significant change that alters the way the images are absorbed and understood by a viewer. I also often edit images to be very active and rapid against a brief silent pause in the music itself. My edits are continuing the rhythm and creating a silent sound that fills that aural gap visually.

Speaking more of de-sync, how do you make it an option in your films?

Swollen Kisses is a good example of how I work with what you are calling de-sync. I created a mash-up of Julie London songs where she is literally singing with herself. I had the idea to do this because I was attentive to Julie London’s phrasing and the distinctly excessive length of time she pauses in between lines of the lyrics. This silent pause was lengthy enough to allow another lyric from a different song of London’s to be sung. The resultant juxtaposition of the lyrics of 2 romantic ballads then creates a new, alternate version of both songs. There is a narrative, poetic openness offered by this approach that encourages viewer interpretation– a new third stream that contains continuities and discontinuities just as my images do.